In late summer I mention to a waiting mom that many of our families pinch every adoption penny, and detail my dream to help kids I’ve met, who without adoption, have futures only of prostitution, crime, drug use, and premature death to anticipate. Her empathy emboldens me, and makes me believe I might succeed. At the end of our conversation, I promise to pursue my plan, thus becoming committed to soliciting funds on a scale which terrifies me.

That night, I begin an outline summarizing our mission, history, goals, and needs. It’s heavy on stories of kids we’ve helped, and those we couldn’t. For the next two months, a focus group of kindred spirits combs every detail with me to ascertain the content is compelling.

When I think I’m done, a veteran fund raiser advises me, “Be good, be brief, be gone,” opining I might have just 10-15 minutes to speak with a potential donor. Brevity has always challenged me, so with sinking heart, I eviscerate the presentation, whittling it from ten pages to four. Afterward, several gracious souls let me practice my delivery on them. I insist on brutal honesty; two are even intrepid enough to point out my annoying mannerisms.

A few in the test audiences see enough potential to suggest the presentation, once polished, be posted on YouTube. I scoff, but mention it anyway to our director Hope, who confesses she’d entertained the same thoughts. Reluctantly, I agree to tape. Several times thereafter she asks how it’s coming. I make excuses, always vowing to work on it during my Christmas vacation from homeschooling.

Vacation comes. Hope is gone, and “work on video” is disconcertingly prominent on my to-do list. Wednesday, a caller inquires about the cost of adoption. After she says it’s too expensive, I note we’re working on a major donor presentation to assist with expenses. She drops the name of a well-known Christian philanthropist she knows personally, and asks if the presentation is available on DVD. I say it will be soon, hoping it doesn’t sound too unbelievable. She says she’ll pray about asking the man to meet with us.

Now there is urgency. I had wanted to finish the video in 2011, but have only four days left. A homemade practice video is proof we need a professional videographer, but I don’t know anyone, and Hope isn’t around to authorize expenditures. Jeff, a recent adoptive dad from Tulsa, does audio recording under the name SongSmith Records. Thinking audio might be close enough to video, on a Wednesday night whim I ask him if he can do it.

I never fathom he’ll say yes.

Providentially, Jeff has been itching to start video recording for the last three years, and just bought the requisite software. He needs a friend to guide him through using it, and a project to practice on. I tell him I need it done Friday or Saturday. He thinks it’s too soon but, hearing my rationale, will ask his friend.

Thursday morning my husband says he’ll drive me from Grand Rapids to Tulsa on Friday if necessary. When evening comes without word from Jeff, I feel more relief than disappointment. But after dinner, there’s a message he can do it Friday, and when can I get there? Foolishly discounting the fifteen-hour drive, I tell him 6 p.m., still doubting he’ll agree. His next message follows at 7:30 p.m. “See you at six Friday night,” it says.

I instantly rue my over-promise. I knew my notes well a month ago, but haven’t practiced since. Driving will require leaving at 3 a.m. Airfare is outrageous, out of the question even if Hope were around to ask. Then I remember the 30,000 bonus miles posted to my Delta account earlier today. Delta.com says 40,000 miles and $10 covers my flight. Problem solved.

I drop into bed exhausted, but adrenaline won’t even let me doze. Four hours later, I’m up, readying for the airport. My trip is a blessed non-event, and I arrive at my in-laws’ house with several hours to study before the evening’s production meeting.

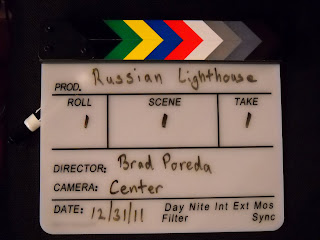

Six o’clock finds me in Jeff’s basement recording studio. A backdrop, large camera, lights, and several microphones alarm me, but the clapperboard labeled with my name makes things nauseatingly real. After several sound checks, practices of my introduction, and admonitions to slow down, Jeff says three of his friends will be helping Saturday. I should be delighted, but paradoxically, as this becomes more professional, I feel more stressed. As I leave, there is little solace at having survived the production meeting, as it is only prelude to what I truly dread. Jeff’s parting words, “Be here at 9:45 tomorrow morning,” ring like a threat.

Back at my in-laws’, I swallow nine Tums in a few hours; I haven’t taken nine the rest of my life. The next morning, I rise early since I’m not sleeping, and my nerves won’t tolerate a last minute rush anyway. I curl my hair, using a generous amount of hairspray from a travel bottle. I haven’t been anywhere since Russia last August, and I’ve forgotten how good it smells. A few minutes later, my hair looks oddly limp and lacks any hairsprayed crispiness, so I spray on more. When I smell the fragrance again, my confidence crumbles as I recall having refilled the bottle with body spray for Russia. Too late, I know why my hair is flat. There is no time to curl again. I can only put on my makeup, and go.

I am leaving when my mother-in-law asks an innocuous question; I start breathing hard and can’t answer. Next, I have a prickly head, and tears are welling in my eyes. “I can’t cry! I’m not going to cry!” I implore myself, as there is no time to clean mascara streaks if tears fall. I threaten to faint while she tries to shepherd me outside into Oklahoma’s omnipresent wind. I am coherent enough to resist, as I intend to salvage the little remaining wave in my hair. Finally, she pushes me into the car, and I calm down in the seat. “Just remember it’s not a matter of life or death,” she encourages me as I depart.

“It’s not, for me,” I agree, hoping she realizes this is life and death for the orphans I’ve met.

Jeff’s friends Brad and Doug arrive shortly after I do. Armed with microphones and cameras of their own, they eventually disassemble most of what we’d checked last night. As they decide where each gadget belongs, I strive to block out thoughts that this is all for me, and that I must deliver to make this worth their efforts. They rearrange the backdrop, overturn a couch, swap chairs, argue about placement of four cameras offering different angles, and call for props. As they work, they refer to me as “the talent.” I understand the lingo, and I am the authority here on my topic, but my inexperience makes the phrase feel hideously satirical.

Doug has a golden voice, and a new NPR show, Wind and Rhythm, to go along. He offers patient pointers on how to modulate my voice for best effect, but my weary, cortisol-addled mind renders me a slow study. I incorporate the hints I can, though most would take me years of practice to perform naturally. I have a large-print outline on a music stand just below the camera’s lens, acting as a primitive teleprompter. As I practice, Doug dislikes my reliance on the outline, so I end up taping short notecards to the stand, and they’re usually sufficient to jog my memory. He reminds me repeatedly that I’m only speaking to one person. I try to speak to the camera, but find it nearly impossible to project emotion to its black hole. Finally, he stands behind it at my eye level, and responds with exaggerated facial expressions to my words.

At 1 p.m., we’re ready to start filming. I am to be looking down when the camera rolls, then look up pensively before beginning. None of it comes naturally, except the mistakes; some elements need five or six takes before I get them right. It isn’t that I don’t know my material; in one sense, I have delivered this speech literally one thousand times, with the call notes to prove it. It’s just the medium is so foreign, and I’m so self-conscious, that the thought of having kids’ lives resting on my performance seems wickedly farcical. Tim, Jeff’s intern, sports enough piercings to look tribal, and an impressive array of tattoos darkens his arms, but he announces each take and scene with a fatherly patience and gentle clap of the clapperboard.

Rare parts of the presentation go almost well, and midway through, I accomplish a few segments where we don’t have to stop at all. But usually, even when I do a section multiple times, we have to settle for the best of several takes as “good enough.” Mercifully, just short of an hour, we’re done filming.

For the next several hours, Jeff and Brad download video from all four cameras. When Brad goes home to care for his dogs, Jeff and I start adding photographs. Timing them properly is maddening, and I wonder if any viewers will appreciate the photos enough to recompense our work. When Brad returns and we start editing, I learn the only thing worse than watching myself on video is watching myself make mistakes on video, while others focus on the miscues to decide which of the takes are least marred. But Jeff and Brad are unfailingly kind, and I never hear them laugh, except when I mess up my ending thank you by proclaiming, “Thank YOU for helping the Russians!”

Our progress is sloth-like, though. It’s New Year’s Eve, my favorite holiday, and I traditionally host a party. It grieves me to miss this; worse, I’m in the Central Time Zone, so I’ll have to delay my first Coca-Cola in a year for an additional hour (The Real Thing, 1/29/11). I’ve been in a 365-day countdown to toast my husband with a Coke-filled goblet at the stroke of midnight.

My mother-in-law knows I am disappointed, so she thoughtfully plans a little shindig for me. But as editing drags on, it’s clear I won’t even make that. I welcome 2012, not with the Times Square ball drop, but by watching the time change on my computer screen. Jeff has a refrigerator outside the studio stocked with Coke, but I can’t bring myself to imbibe without my husband. The moment I’ve ached for is here, and I’m in a basement control room. I almost start crying, but compose myself since Jeff and Brad are giving up their New Year’s Eve, too, and Lighthouse is not even their mission. I fret that by the time I leave, drunks will be out, and I’ll never get to see my family, drink my Coca-Cola, or help my orphans. About 1 a.m., Jeff’s wife delivers pizza, which cheers me as I hear myself intone about the orphan prostitutes of Russia for the umpteenth time.

For the end of the video, I’ve envisioned a quick photo progression of kids our work has helped, accompanied by the sound of cards shuffling. But for the thousands of sound effects on the software, cards aren’t one of them, so Jeff tries valiantly to create it himself. Brad hears the result and frowns. “You can’t use that! It sounds like farting!” he chides, suggesting a xylophone instead. Jeff searches online, and eventually finds an ascending chromatic scale. It’s perfect.

At 4 a.m., the parts needing my input are completed. Brad has fussy touches to finish, and thinks it will go faster if he is alone. I lay down on a couch in the recording studio, bemoaning the hour, yet solacing myself that the drunks will be home before I leave. I never really sleep; I just listen to my spiel ad infinitum as he works.

At 6:30 a.m., dear Brad is done. As he gives me a hug before leaving, I could almost cry that he gave up so much time to help our orphans, when he doesn’t know them, or me, or the Lighthouse Project. I thank him profusely; he’ll never know how much I’ve appreciated his help and expertise. While I didn’t give him much to work with, he has done a technically masterful job.

Jeff still has to copy the discs. When the first is done, he asks me to watch it. How many things I wish I would have worded differently, or could have written rather than spoken! I am not satisfied with my performance, but thankfully, it isn’t terrible with the most egregious errors edited out. After the second copy is made, I finally stumble to the car. The clock on the dash says 8:00 a.m.; we have worked on a 19-minute production for just over 22 hours straight.

I’m in a fog, but I drive slowly and meet only churchgoers on the road. Arriving at my in-laws’ house, my father-in-law comes out to greet me. I see him, and start to sob hysterically. I have been waiting all night to break down; the pressure of orphans needing me succeed at something so stressful is too much to resist longer.

Three hours later, smeared mascara washed from my face, I board the plane in Tulsa to return home. I can scarcely believe this video ever got made, especially under such crazy circumstances. Furthermore, the quality is far superior to anything I dared plan when Hope first asked me to do it. My heart might explode waiting for her return, so anxious am I to let her know not only did we work on the video as promised, we also finished it.

Arriving home Sunday night, I’m too spent to do anything besides collapse into bed. The next day, January 2, I cook my favorite dinner. With my family gathered round the table, I pop the top on my first Coke in a year and a day. I close my eyes and relish the fizzy assault on my nose. I could attack the Coke, but I delight instead in my deliberate control, knowing I am crossing my Rubicon. When I’m ready, I take one sip, and then another. It is thick, cloyingly sweet, and artificial. I don’t like it, not at all.

Arriving home Sunday night, I’m too spent to do anything besides collapse into bed. The next day, January 2, I cook my favorite dinner. With my family gathered round the table, I pop the top on my first Coke in a year and a day. I close my eyes and relish the fizzy assault on my nose. I could attack the Coke, but I delight instead in my deliberate control, knowing I am crossing my Rubicon. When I’m ready, I take one sip, and then another. It is thick, cloyingly sweet, and artificial. I don’t like it, not at all.I pour a glass of cold water and drink deeply.

Somehow, I’ve survived.

See the video here.

Tweet